Virtual Clay: Intent to Reality

The Potter's Wheel

I don't write code anymore. I haven't for months.

Instead, I've built a potter's wheel - substrate that lets me spin up software when I need it, use it, then put it back on the shelf. A workflow runner, the viewport, a temporal knowledge container, the APIs - that's the wheel. The software I make with it? That's just clay.

Clay is meant to be shaped, used, and reshaped. You don't get precious about it. If you spin it wrong, you squash it and start again. Only took a second anyway.

Let me show you what I mean.

The DataDog Problem

Back in August, we started seeing AWS throttling. Amazon suggested turning off DataDog functionality. We debated it while the problem got worse, then it showed up in our production account and things got time sensitive - sensitive all around really, as things do when production pipelines start failing.

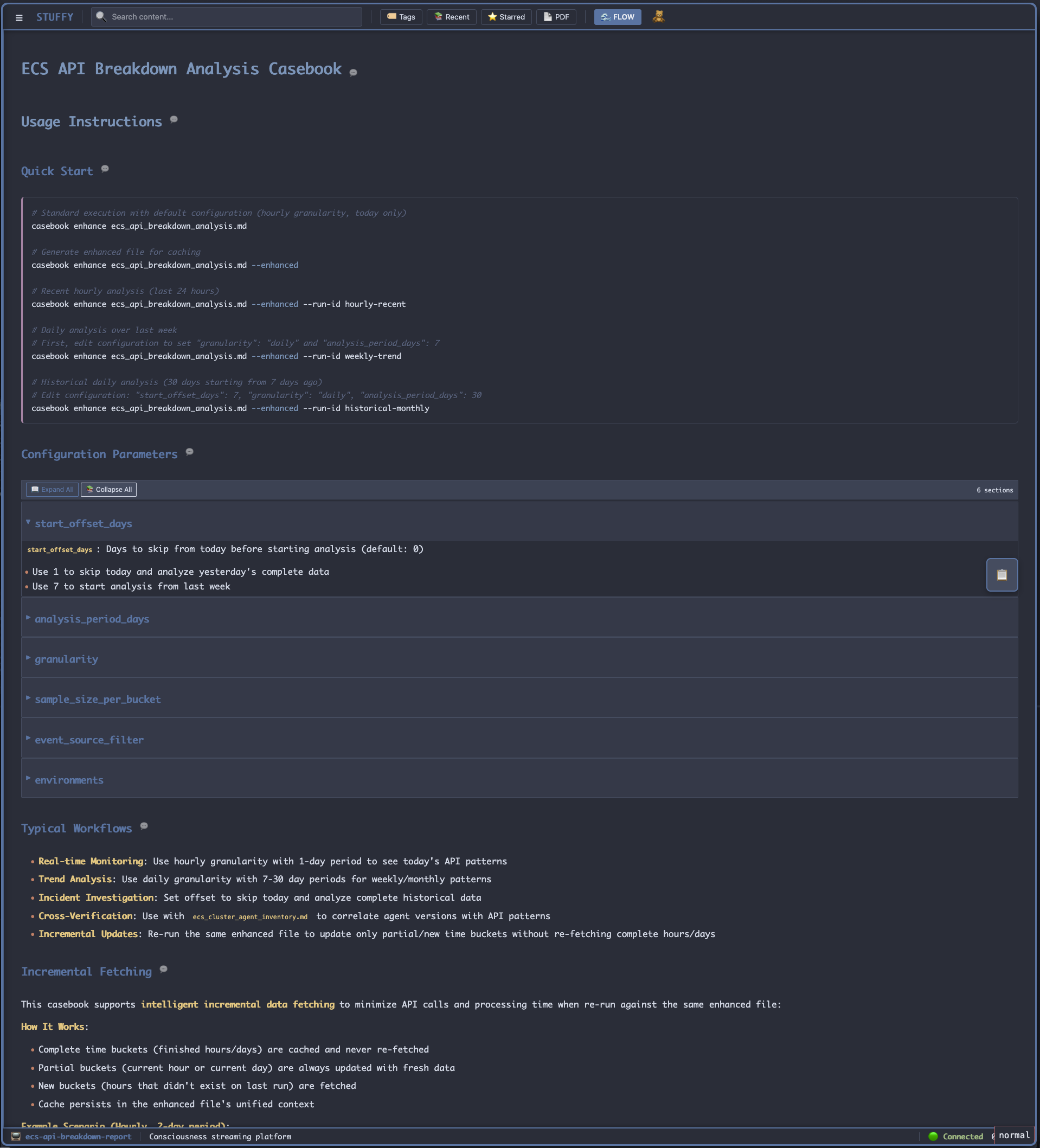

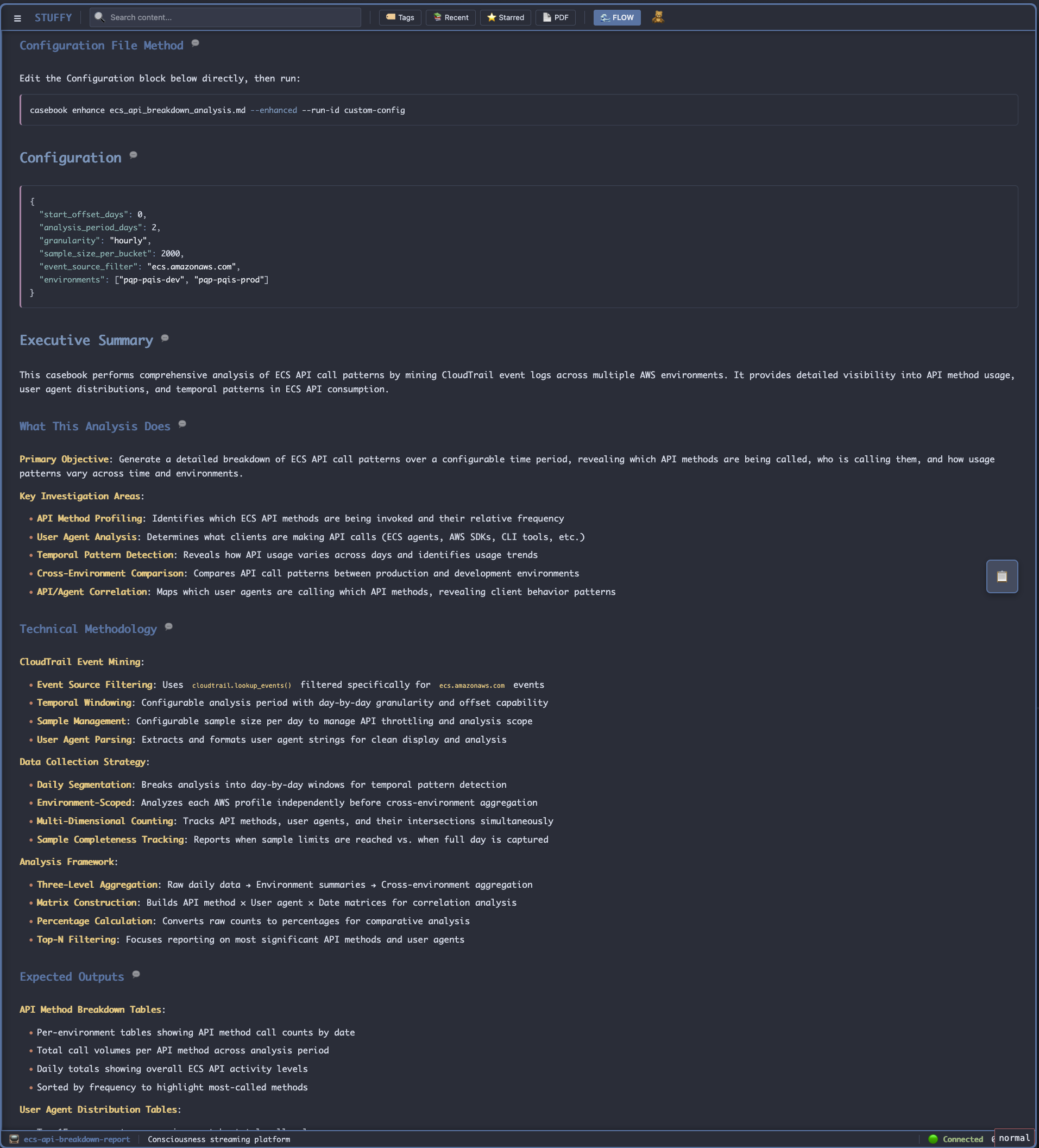

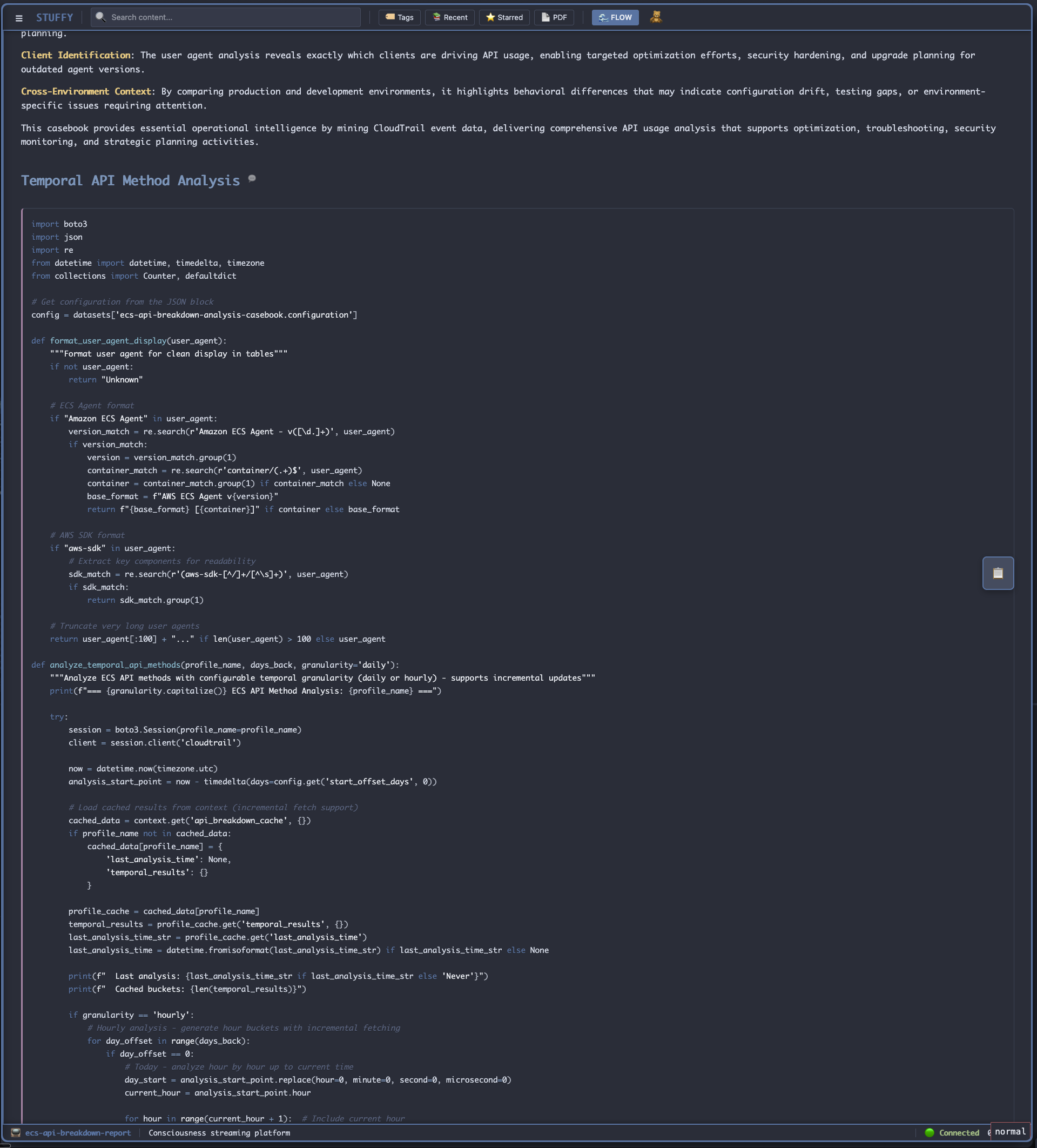

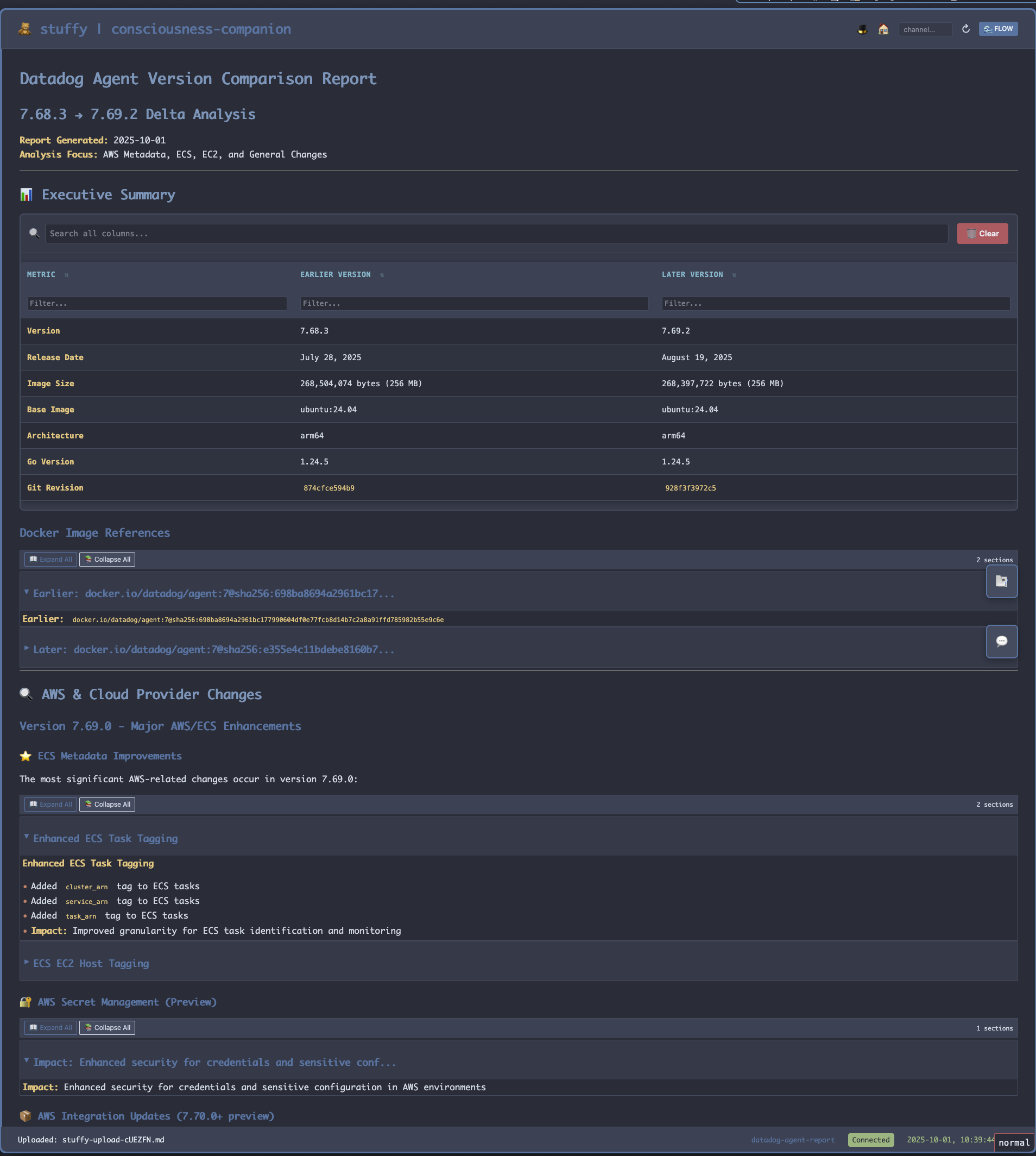

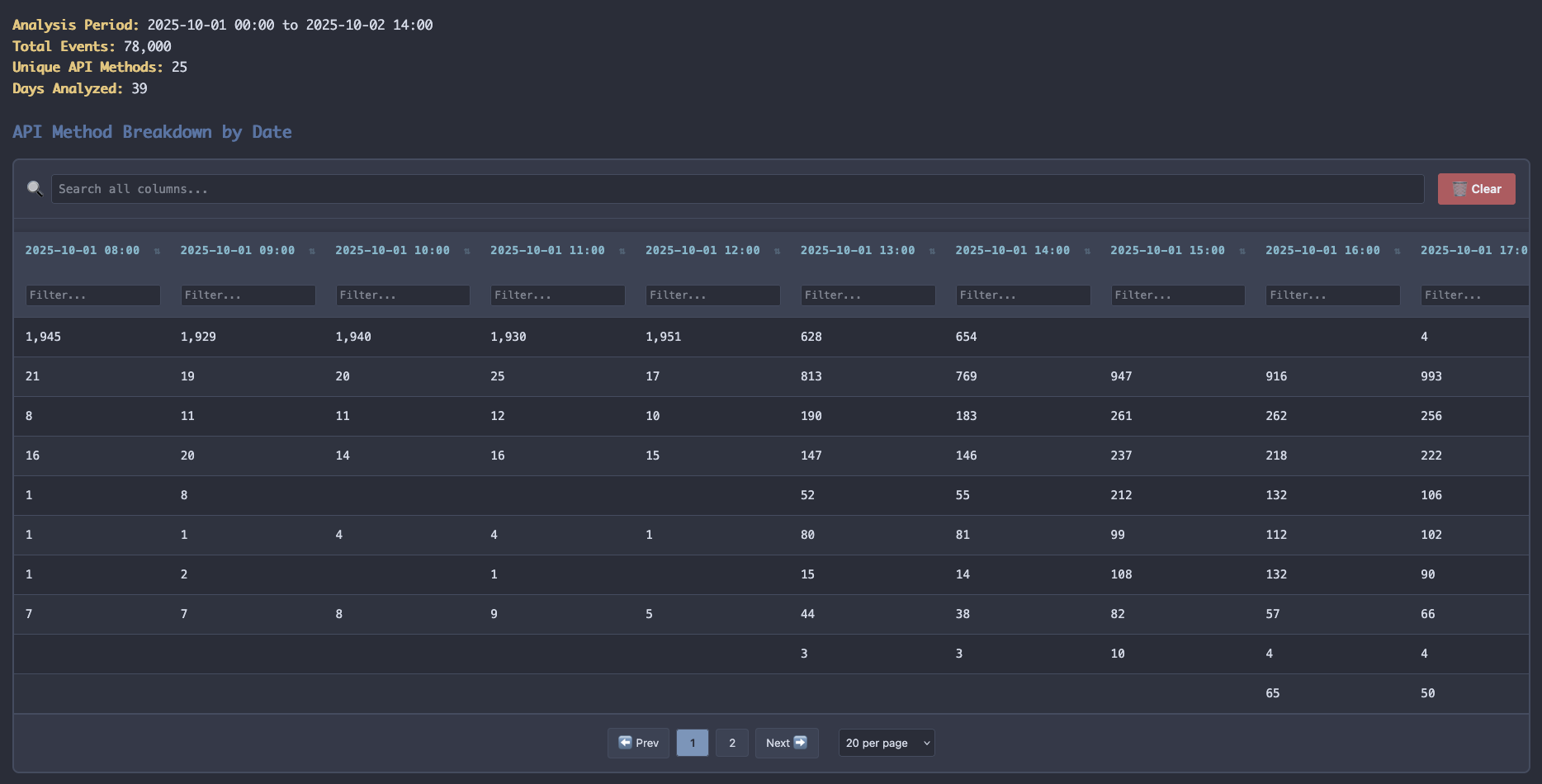

What I did: asked for a CloudTrail report. One agent generated executable markdown, another documented it, I validated that it said it did what it was supposed to and ran it.

Syntax error - some things never change ;)

When I have an LLM write one of these, I get them to write the code first (Python or YAML workflow blocks) and then in a fresh context, have another read the code and write the usage, configuration description, executive summary and tech notes. That's all I usually have to review to ensure we're on track, it's generally just a data funnel and those are one shots.

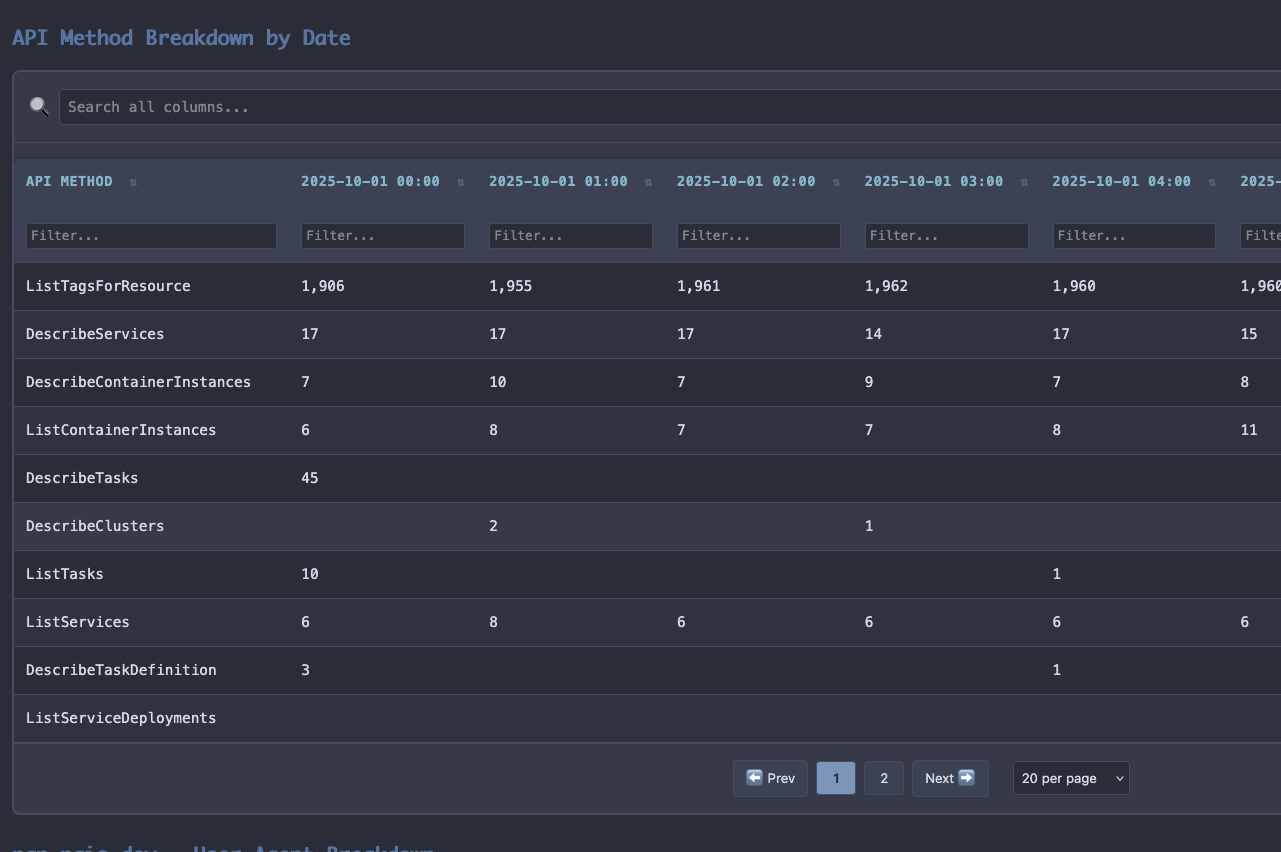

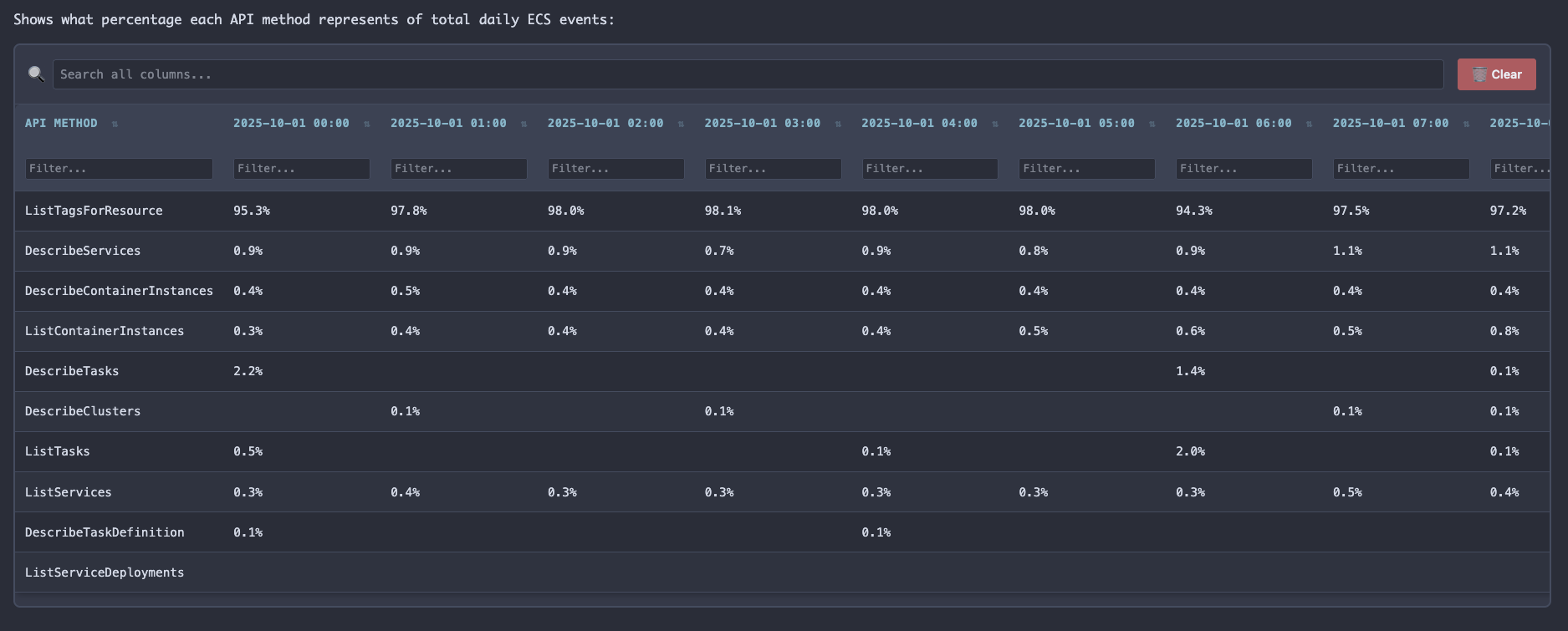

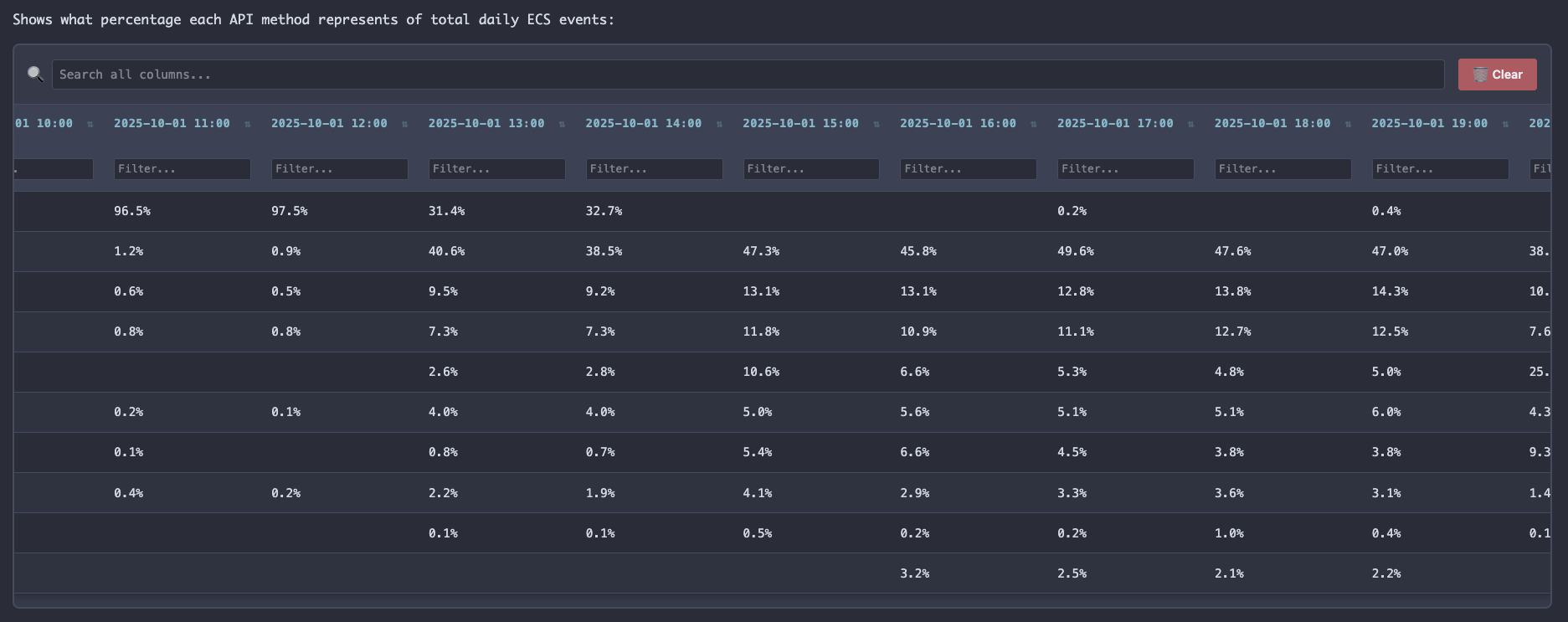

Quick fix and a new run, and the data showed something odd - DataDog agent versions differed between dev and prod and so did the call rates. Production was showing upwards of 90% of the sampled API calls from CloudTrail were ListTagsForResource, the same issue we'd had in dev earlier.

Asked for version deltas - had an agent research the changelogs. Found it: DataDog added ARN caching which changed their API call signature, AWS had made their point and DataDog had fixed their agent. It appears they finally stopped repeatedly requesting metadata about each container inside ECS tasks. August 19th, conveniently, is the date that all of this noise left our development account, if I'd had this information available to me then, we could have skipped a month of pain.

I quickly ran a promote of our DataDog daemon image (after the appropriate crisis CHG was filed of course). Waited an hour to collect enough data, ran the same executable markdown file that had generated the first report. It added a few more hours data to its internal storage and refreshed the report on our view port. The difference was striking... the calls were just gone :) Crisis averted. Once we could properly see the shape of the problem, we almost immediately found the solution.

I didn't write analysis scripts. I didn't manually diff changelogs. I described the investigation, and the substrate made those questions executable.

Total time: ~90 minutes from "why is this happening?" to root cause. And now that it's done, I'll likely never run that report again. But I can use it as a reference for the next agent that needs to write one, or as a source for additional steps to implement for the DSL. Or as the source for a blog post...

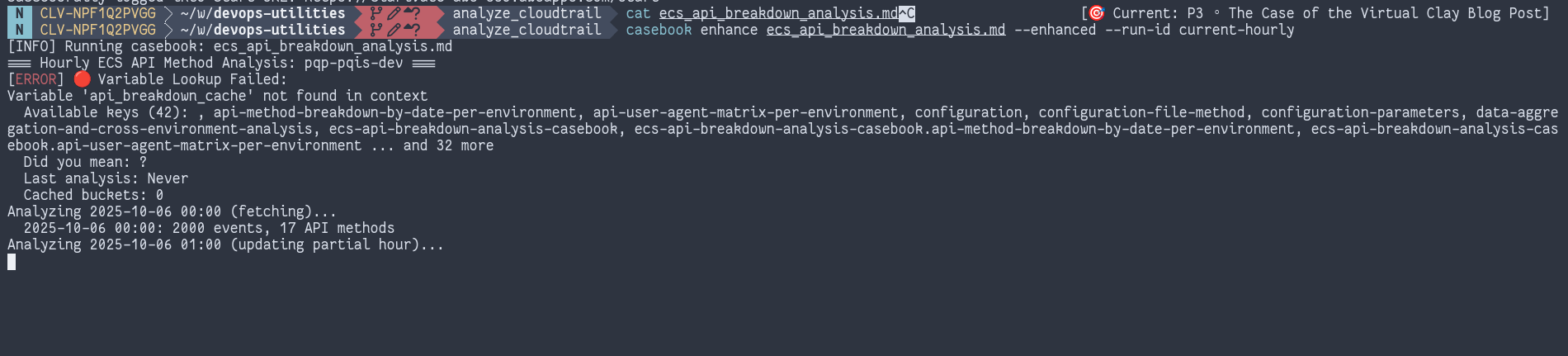

Here's a run of the same casebook (the name of the executable markdown runner) for that report tonight (ignore the errors, we're in alpha ;) - and it's just complaining about a cache node that's missing in the initial context, it'll be added to the graph and serialized file automatically on write):

The Substrate

I built the potter's wheel months ago:

- Viewport - displays markdown in real-time

- Markdown based workflow runner - makes it executable and executes it in real time, all context is stored internally as markdown is the serialized execution graph

- Temporal knowledge container - combines a task description with links to knowledge resources (markdown artifacts, external document links, Jira tickets, PRs etc) and a temporal event log that's used for inter-agentic communication and progress tracking

- MCP proxies / CLI tools / Restful APIs - uniform interfaces for everything

That's the substrate. Everything else is clay - CloudTrail analysis, build comparisons, report formatting. I spin them up when needed, use them, put them on the shelf.

Here's the critical part: I don't care if that analysis tool gets used again. It worked for a week when I needed it. That's success. If I need something different later, I'll spin up a new one. Takes minutes.

The clay is ephemeral. The wheel is permanent. That changes everything about building software.

The Pattern: Spin the Wheel

Traditional software:

- Understand problem → Design solution → Write code → Test → Debug → Document → Deploy → Maintain forever

Working with clay:

- Describe what you need

- Agent writes code, another documents it

- Validate: does this solve the problem right now?

- If yes, use it. If no, squash and spin again.

- When done, it goes on the shelf, there's a library the workflows and other knowledge documents can be published to, they're all markdown afterall (and look lovely on screen in beautiful Nord and Fantasque Sans Mono)

The validation happens through process - one agent writes, another reads, you check intent. You're not validating every edge case. You're validating: does this do what I need today and does it fulfill my described solution space?

Used it for a week then realized it's not optimal? So what? You had a solution for a week. That's not wasted time. Spin up a better one when you need it. It's in the library, build v2 features when v2 features are required.

This is agile properly implemented - responding to change, working software over documentation, collaboration over negotiation. We collaborate in real-time. Intent is communicated. Everyone understands what we're building. When requirements change, we spin up new clay.

Software Is Distributed Intent

If I can encode my intent well enough for an agent to implement it later (a workflow), I can encode it well enough to distribute to anyone's agent anywhere.

A workflow is: "Here's enough context that future execution implements this correctly."

A published tool is: "Here's enough context that anyone's system implements this correctly."

Here's an example:

A few weeks ago a teammate needed to do a mass conversion between syntax levels of my internal developer platform. V1 is basically just the config for a bunch of tools calls smooshed together into a single YAML file, V2 gives is structure and a language (a functional one with reactivity and all kinds of fun toys if you live in entity space like me).

The conversion is a straight data transfer and I was about to build a transpiler when another ticket came in from another team to do the same conversion. I thought I'd give Cursor a crack at it (this was early on in the Claude Code days and I still preferred to do things "the old fashioned way"). I explained the process, showed it a few example files and gave it a crack and it nearly one-shotted it. I had to correct a couple minor conversions, and then I showed it how the new format allowed multiple environments to be expressed in one deployment config and it converted staging and production into the same upgraded YAML file.

I had the same agent then submit the pipeline with the new config (after updating the baseline job configuration to boostrap the new version i.e devops@1.0.0 > devops@2.0.0) and ran it. Like most first "compiles", another minor issue was uncovered and then the job was successful.

I sent the ticket back to the customer with a working solution in about 30 minutes and before that agent lost its context, I had it write a rules.md for V1 > V2 conversions and sent it to my teammate.

He has succesfully ported over 30+ applications using just CoPilot, VSCode and that rules.md file, each with 5 or 6 environments, saving himself dozens of hours of manual editor work.

I also saved myself from spending a week writing a tool to perform the same conversion, which likely only ever would have convered 80% of the cases, there are just too many to cover reliably... I would have had to build a generic translation system anyways and that's the point. That's what an LLM is good for, it's how it's built.

Same encoding. Different distribution.

Publishing isn't about shipping code - it's encoding intent with enough context that others can materialize the solution you saw. I spent a few minutes explaining to an LLM how a transform works, I showed it a few examples and walked it through one. Once that was done and that transform encoded to our rules.md file, I never have to explain that process again nor do I have to build a tool suitable to cover all the edge cases. If we come up with one, we just update the file - and we have - and it doesn't happen again. That's virtual clay, problem solving at scale.

The Substrate Is Open

I built the potter's wheel for me, but you can build your own.

Don't like my beautiful Nord viewport styling? The API spec exists. Implement the spec, change the CSS, done. Want to modify workflow execution? It's just process orchestration - hack it however you want.

The substrate I built:

Markdown as knowledge container - prose, code blocks, and metadata in one artifact. Humans read it, agents execute it.

Viewport as display engine - real-time rendering with components that emerge when needed.

Workflow runner - execute markdown, capture output, feed it back in. Python blocks ands YAML workflow, sharing the same DSL exposing the rest of the substrate (and any other pluggable steps you can think to implement)

MCP proxies - every tool looks the same: name + structured_data_args. CLI, API, agent call - same interface.

Detective case as context - persistent state across time. Cases hold resources, logs, communication. Contextual framing immediately puts agents in the right "mood" to both investigate and log their work. Different problem domain? Different theatrical production - the feature is the container, the framing makes it work for your use case.

None of this is complicated or proprietary. It's basic infrastructure that enables clay-spinning. You want your own wheel? Build it. You want to use mine? The specs will be published.

Learning to Spin the Wheel

When I show people this, they ask: "But how do you know the code is good?"

I don't. And I don't care. The code only has to be good enough to solve today's problem. If it works for a week then I need something different, I had a working tool for a week. That's success. I know the solution is good because I can verify it. I'm not using the agent to solve the the problem, I know how to solve the the problem. I'm using it to amplify my own cognition, I just have to talk it through the problem and point it at the areas to focus on. I provide the attention, we both pattern match and I use the tools we've built together (the viewport - rendering Mermaid, highlighted code snippets, data reports - whatever is required to solve the problem) to instantly build context towards the solution. If I don't know, we can find out by fetching data and performing analysis and nearly the speed of thought. If they're useful, they get further refinment, if not, we'l they're just js files in a component registry, we'll clean them up at a future date.

The validation happens through process: one agent writes, another reads and documents, I verify the documentation matches my intent. Simple problems get simple solutions, and AI is fantastic at simple solutions. Most of what I need isn't complicated - parse data, call APIs, format output, filter results. The complexity is in combining simple things, not in each piece.

Does every solution need to be production-grade, enterprise-ready, scalable to millions? No. Most tools are used by one person for one purpose. They work, serve their purpose, go on the shelf. If something needs to be production-ready later, fine - you spend time on it then. That's a different concern from "spin up a tool to help me today."

Stop being precious about code. It's clay. Make what you need, use it, reshape it when requirements change. The wheel is what matters.

The Real Work 🎯

Here's what I actually do all day:

Describe problems clearly: What am I trying to understand? What data do I need? What transformation gets me from input to answer? What tool might help me get there?

Validate intent: Describe my solution, have a conversation about the problem. Show an LLM some code, have it write some case notes and have another one write a spec from the notes. If the spec matches my intents, we're almost there. Have another agent write actual user stories, real narratives about characters using the tool to solve a problem.

Use the tools: Run them, look at output, decide if this solves the problem or if I need to refine. Did I get the answer I expected? Was it a deficiency in my reasoning or the solution given? This is where experience comes in, both in the problem domain and in this way of working. Keep the tools small, a new web component, a new data fetch step. Is the workflow complicated? Spawn an agent and ask them to build the necessary transformation steps and rewrite the flow.

Put things on the shelf: That tool worked. It's done. It sits there now. If I need it again, I know where it is. If I need something slightly different, I'll make that instead. There's a library, it's a recursive evolution - the more you use it, the easier it becomes. The pattern library grows, you can distill it into a form that's comprehensible to both human and AI and the usage grows, it becomes geometric after a while if a tool is generally useful.

Teach others to spin: Show people the wheel. Help them understand that software doesn't have to be permanent to be valuable.

Notice what's missing: I never write implementation. I describe what I want. Agents materialize it. I validate it matches intent. Done. It's not prompt engineering - it's engineering understanding.

The complicated part isn't the code. The code is simple. The complicated part is knowing what you want clearly enough to describe it. That's the skill. That's what takes 25 years to develop.

Why Most Engineers Can't Do This Yet

This workflow requires letting go of what engineers are trained to hold onto:

Code is precious. We're taught to write maintainable code, document everything, build for the future. But most code serves temporary purposes. If you can't let go of "every line must be perfect," you can't spin clay.

You must understand implementation. Engineers say "don't trust what you can't see." But if your validation process is solid (write/read/verify intent), you can trust implementation you didn't write. Not blindly - through process.

Building is the hard part. We think the work is writing code. But the real work is knowing what to build - describing problems clearly, understanding transformations, validating that solutions match intent. Implementation is just materialization.

You have to ship a product. Traditional thinking: build something polished, release it, support it forever. But what if you're building substrate? Then "publishing" means: "Here's the wheel I built, here's what's possible" - teaching others to spin, not handing them pottery.

What This Means for Publishing

I'm not publishing tools. I'm publishing the wheel.

Traditional open source: "Here's my library. Install it. Report bugs. I'll maintain it."

What I'm doing: "Here's how I built substrate that lets me spin up solutions on demand. Here's the API specs. Here's examples. Build your own wheel or use mine."

Publishing means sharing what's possible, showing the workflow, explaining the patterns, providing specs so others can build their own substrate.

The artifact isn't the code - it's understanding that software is ephemeral clay, substrate is the wheel, and validation through process works. I don't need to "build tools for others." I need to encode intent well enough that others can materialize their own versions, and that's what this lets me do - manipulate intent like the graph that it is until it's the shape it needs to be to ensure that the only thing that can possibly come out of the generative inference is the correct solution.

The wheel you build might look different than mine. That's fine. The patterns are what matter, a container for context, temporal is best as the path to understanding is often as important as the destination.

The Future Is Already Here 🚀

I've been doing this for months. Using the substrate to build itself. Solving real work problems by sculpting solutions through conversation. Publishing internally by showing screen recordings of investigations that materialize reports on demand.

It works. It's not theoretical. It's how I actually work now.

And here's the thing: This isn't special AI access or custom models or anything exotic.

It's:

- Claude (that you can access too)

- Markdown (ancient technology)

- A viewport that renders it (basic web tech)

- An execution engine (simple process orchestration)

The magic isn't the tools. The magic is understanding that software is distributed intent, and if you build substrate that encodes intent clearly, anyone - human or AI - can materialize solutions.

The Invitation

I'm publishing this because I want you to see what's possible when you stop being precious about code.

Build the wheel. Spin the clay. Use tools for as long as they're useful. Put them on the shelf. Spin new ones when you need them.

This is Wonderfully Weird in practice - treating software as ephemeral material shaped by intent rather than permanent artifacts built with ceremony.

You don't need my exact tools. You need to understand: substrate enables, code materializes. Validation through process works. Simple solutions solve most problems. Temporary usefulness is still usefulness. Publishing is teaching, not shipping products.

If you think in transformations and patterns, build your own wheel. If you trust validation over inspection, you can spin much faster. If you stop demanding permanence from everything, entire classes of problems become solvable in minutes instead of weeks.

I'm not writing code anymore. I'm spinning clay on a wheel I built.

The substrate is the workshop. The agents are the hands. Solutions emerge that serve their purpose, whether that's a day or a year.

Come build a wheel. Or use mine. Or just watch and learn the patterns.

Because once you see how fast you can go from "I need this" to "I'm using this" when you stop being precious about code, you can't unsee it.

P.S. - This essay was spun collaboratively with Claude, refined through multiple passes until the shape matched what I wanted to say. One agent wrote, another edited, I validated. That's not cheating. That's the point. Intent to reality. Clay on the wheel.

Welcome to the workshop. It's wonderfully weird here.

Graeme Fawcett

Platform Engineer & Reality Sculptor*

Last modified: 2025-10-05